What Happens When You Teach Kids That Wildlife Is Worth More Alive

Children in the Bush Babies Environmental Education Program show off their coloring pages of meerkats. Image by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

Inside Kruger National Park, a child sees an elephant for the first time. Wide-eyed, she watches as the massive animal trudges through the dry grass, ears flapping with each slow step. It’s silent as the students of the Bush Babies Environmental Education Program sit in awe. Some grip their notebooks. Others lean forward, not wanting to blink.

For many of these children, it’s the first time they’ve been inside Kruger—a vast, 7,500-square-mile wildlife reserve along South Africa’s northeastern border. Though the park borders their villages, it has long felt out of reach. This is the first time anyone has told them they belong here.

And for the team behind the Bush Babies program, moments like these are everything.

At its core, the program is about fostering connections—building relationships between children and the wild landscape they live beside.

Craig Spencer, founder of NGO Transfrontier Africa and the program’s visionary, spent over a decade in paramilitary anti-poaching efforts to save rhino populations prior to the organization’s formation. Sadly, the results were disappointing, and the collateral damage of burnout, bloodshed, and community distrust was too high.

A rhino grazes at the Hoedspruit Endangered Species Center. Its horn has been safely removed to deter poachers—a tactic in high-risk areas.The horn, made of keratin like a fingernail, eventually grows back. Image by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

As poaching syndicates became more sophisticated, so did the response. Spencer watched as conservation turned into an escalating arms race. Each side adapted to the other with heavier weapons, but the rhino numbers continued to fall and people suffered. “A natural area should not be a place of bloodshed and generating PTSD,” Craig said.

The approach alienated the very communities that surrounded the parks. Most had been excluded from conservation decisions since the days of apartheid, and many still lived in poverty with little access to jobs or services. Spencer realized that protecting wildlife couldn't come at the expense of the people living beside it. “We needed a novel approach that would have a long-lasting impact,” Spencer said. “We were fighting poverty, moral, and social decay.”

That new approach became the Black Mambas: an unarmed, all-female ranger unit recruited from local villages near the Greater Kruger National Park—a conservation area that includes Kruger itself as well as surrounding private reserves that work in partnership to protect wildlife.

At the time of their founding in 2013, South Africa was in the midst of a rhino poaching crisis. Driven by black market demand for rhino horn, poachers were decimating the species across the region.

Black Mamba rangers Yenzekile Mathebula, Loveness Mongwe, and Belinda Mzimba (left to right) smile by their patrol vehicle during their morning snare sweep. Image by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

The Black Mambas stepped into the bush armed, controversially, with only handcuffs and pepper spray. They patrol the fence lines of Olifants West Nature Reserve, dismantle snares, report suspicious activity, and serve as role models to the young girls and boys watching them in uniform. According to Helping Rhinos, since their formation, poaching in their patrol area has dropped by more than 60 percent.

As impactful as they were on the ground, just a few years after forming the Mambas, Craig and Black Mamba ranger Lewyn Maefala realized they couldn’t wait a generation to shift values. They needed to start younger.

“Without the Bush Babies, we would have to wait for the Mambas to become grandmothers to influence the next generation,” Spencer said. “Too late for the rhinos.”

So they created the Bush Babies: a year-round environmental education program taught by Mambas themselves, celebrating a decade of impact this year. The name “Bush Babies” comes from a small, wide-eyed primate native to the region. It reflects both the children’s sense of wonder and their close connection to the bush—the wild landscapes just beyond their doorsteps.

The Bush Babies Environmental Education Centre sees its first students arriving for the day. Image by Olivia Lockett. South Africa 2025.

The program operates every Friday afternoon at a dedicated center where students receive lessons and a hot meal that, for many, might be the only one they have that day. Beyond the center, Mambas regularly visit local schools to teach about conservation in places that otherwise may have little access to environmental education. They bring the knowledge of wildlife closer to children in remote communities, exposing them to ideas that previously remained out of reach.

Bush Babies pose for the camera with their meals after a day of learning at the center. Image by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

The Bush Babies program also offers field trips that take students into the bush for game drives and overnight camps. Black Mamba ranger and educator Tsakane Nxumalo said some of her favorite moments come when the children are camping, hearing animal sounds in the night and guessing what they might be, or when they draw their favorite animals after a drive. “I’ve noticed differences in the children after joining the program,”she said. “They have respect for the environment now. Especially with cases like littering. They do community service and they know if you litter today, they’re coming to pick it up tomorrow.”

With every classroom visit, game drive, and achievement badge earned, the Bush Babies program is working to break a cycle of violence. According to Nxumalo, poaching often draws in young people from the same communities, but Bush Babies gives them another path. It replaces destructive forces with pride, knowledge, and a positive future — one where conservation is not just a distant ideal but a tangible possibility, and it starts with these children.

Black Mamba ranger Naledi Malungane teaches Bush Babies about the seasons. Image by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

Nxumalo’s own path to becoming a Black Mamba and educator began in 2019, fresh out of college and unemployed. She came across a Facebook post about a job opening. “I saw it and thought, this is crazy—how do you walk in the bush without a firearm?” she laughed. But with little else to do, she applied.

Portrait of Black Mamba ranger Tsakane Nxumalo. Photo by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

After interviews and preliminary fitness tests, she was hired. Then the real work began. Training to be a Black Mamba ranger was brutal for most of the women. They survived grueling fitness tests, lived in the bush, and ran in the heat with barely enough water. “It was very hard. I went home two sizes smaller. But it took the ‘I can’t’ out of us,” Nxumalo said. This training is what sets the Mambas apart from other rangers. “We have a sisterhood from training. You can't do anything alone in the bush. It pushed us to work as a team,” she said.

Now 30, Nxumalo serves as both a senior environmental educator with the Bush Babies program and a sergeant with the Mambas’ crime prevention unit. She teaches school children lessons about the dangers of poaching to personal safety and first aid skills. In the evenings, she studies for her education degree online, and with help from her parents, raises her 1-year-old child.

She remembers when her family struggled to understand her work. “They saw animals killing people on TV. My mom would beg me to come home,” she said. “But I couldn’t. I had the training. I had the knowledge. So it became my job to teach them what they didn’t know—to help them trust that I was safe.”

Black Mamba ranger Naledi Malungane walks through the bush on the lookout for snares set by poachers. Photo by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

Nxumalo’s sense of duty to inform and protect carries into the classroom. “Poaching is happening in South Africa. These kids come from places where poachers are neighbors, sometimes even family,” she said. “But we teach them to think differently. You don't have to go down a path where there's imprisonment, there's guns, there's danger. You can grow up to be like me.”

Despite her leadership, Nxumalo still finds herself pushing back against assumptions—especially the idea that only armed men can do this work. She believes the opposite is true. Carrying weapons, she says, can create a false sense of control. “A lot of rangers that are getting killed are rangers that have weapons,” she explained. Instead, the Mambas rely on a deep knowledge of animal behavior, discipline, and the local youth. And above all, she added, “Our genders do not define our capabilities.”

This extends beyond the bush and into the community, where Nxumalo sees the Bush Babies program as a vital force for change. To her, it’s more than just environmental education. It’s a lifeline breaking destructive cycles. With drastically fewer snares found today and more students inspired to protect rather than poach, she knows the message is landing.

Scouts pose with an elephant statue during their field trip to Kruger National Park with the Bush Babies and the Global Conservation Corps. Photo by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

“I wouldn't want my kid to see on TV that there was once a rhino, or there was once a pangolin,” she said. When animals disappear, it’s not just ecosystems that suffer. Opportunities vanish too. “By killing these animals, they're not only making the animals go extinct,” she said. “Our children who wish to become rangers, to become conservationists—they would have nothing to conserve.”

By teaching children now, she believes it’s possible to change that trajectory. With knowledge, care and courage, a new generation can grow up not only with something to conserve, but with the power and knowledge to protect it.

Black Mamba ranger and Bush Babies educator Sevy Mboweni teaches kids about hiking safety. Photo by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

That message resonates with others in the field too—including Mbhoni Mzamani. His path to conservation began with a moment of regret. As a child, he caught a bird—the southern-masked weaver—but after seeing its beauty up close, he felt pity. “I dug a hole, and buried it. That was the last time I took a life intentionally,” he said. He calls that moment a turning point—“a moment where I was born again into conservation.”

Today, he serves as the head of community engagement at Global Conservation Corps (GCC), where his work focuses on building long-term relationships between local youth and the landscapes surrounding them. It’s a mission deeply aligned with the Bush Babies Environmental Education Program, simply operating in a different region.

Their shared vision came together in June 2025, when the Bush Babies and GCC joined forces for their first collaborative outing: a field trip into Kruger with the oldest Bush Babies—known as the “scouts.” The students experienced a game drive, met wildlife up close, ate warm meals, and heard lessons from both the Black Mambas and Mzamani himself. “That trip represented possibilities in the eyes of the kids,” he said. “It represents the chance to make a tangible difference on the planet.”

Scouts show off their animal drawings during their field trip to Kruger National Park. Photo by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

Both programs recognize the importance of giving children direct, meaningful encounters with wildlife—especially those living right on the park’s edge who have never been granted access.

Poaching, he explains, is often driven by desperation, proximity and a lack of knowledge. “You’ve never been into the park. Rhinos mean nothing to you because you know nothing about them. Your family hasn't had protein in a month. What then?” Mzamani asked. “Eventually, you go into the bush. You go look for a rhino horn. As rangers, we arrest you. Does it solve the problem? No.”

That’s where early education steps in. The Bush Babies program begins working with children as young as 3 years old to 18 years old, using age-appropriate lessons to instill care, curiosity, and respect for the environment. GCC shares this goal, but they specialize in grade seven and beyond, introducing conservation as a possible livelihood. Both organizations share the goal of long-term transformation—breaking harmful cycles before they begin.

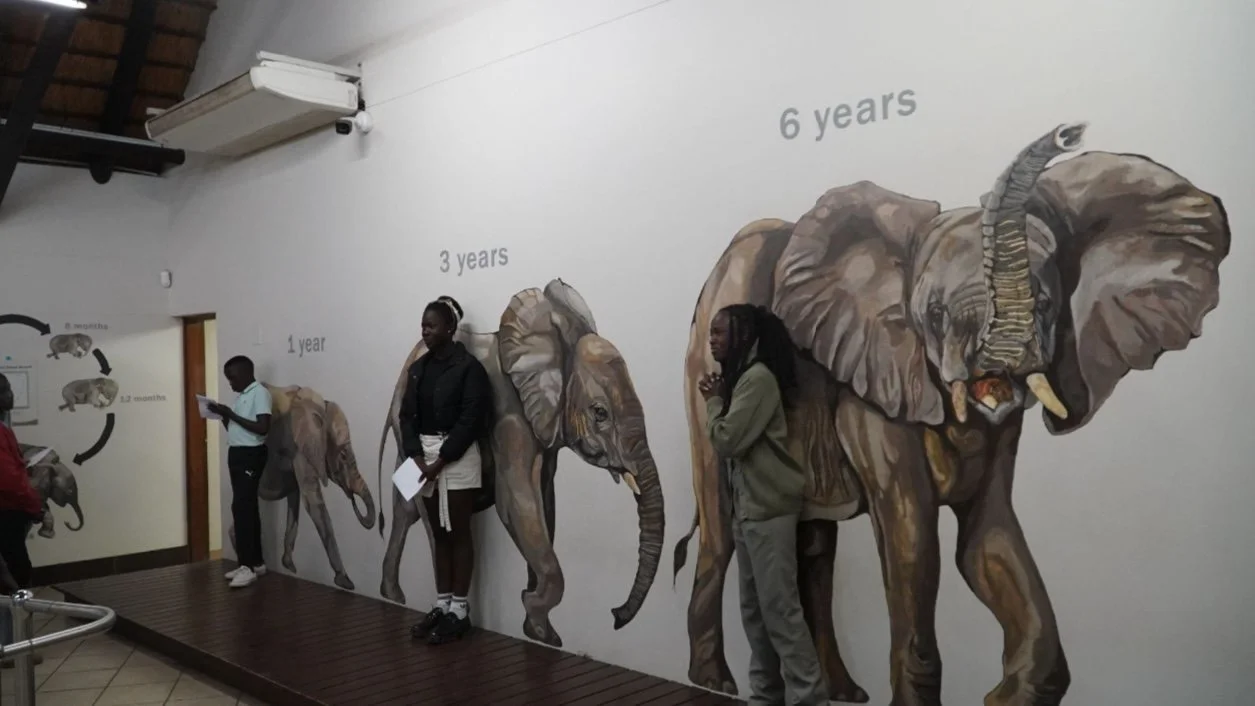

Scouts compare heights with elephants in Letaba Elephant Hall at Kruger National Park. Photo by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

“If the kids see the opportunities that exist within the conservation field and eventually benefit financially,” Mzamani said, “now we are creating a social fence”—one that helps communities say no before violence becomes a last resort.

Both Mzamani and Nxumalo agree that children need more than lessons. They need people to look up to. “Whenever I stand in front of the kids, I'm a role model, and they look up to me,” Mzamani said. “We live in the community. They're looking at us, and they don’t close their eyes after school.”

Programs like the Bush Babies give students that visibility and a reason to believe that conservation can offer them a future. “We may be different organizations,” Mzamani said, “but the main goal is the kids. Whatever helps the kids, we do it.”

Tsakane Nxumalo describes all the aspects of the Bush Babies Environmental Education Program at the center. Photo by Olivia Lockett. South Africa, 2025.

If more conservation programs were built like this—rooted in communities, led by women, and centered on children—Spencer believes the impact could ripple for generations, far beyond the boundaries of Kruger. “It’s the only way to build a resilient protected areas network. We can't fortify the parks and re-enter an arms race to protect wildlife,” he said. “It has to be a joint responsibility with local communities and the primary caregivers who are responsible for children's welfare.” True success, he added, isn't just counted in rhinos saved, but in rangers who choose this work, and in children who grow up seeing a future in conservation.

“Everyone has an obligation to make a sacrifice for conservation,” Spencer said. “Don’t sit back and leave it to the rangers.”